DEFINING 'GOOD' & 'BAD' AREAS

Every city has areas where newcomers and visitors are told to avoid. Often, they’re defined by low-income housing, or a perceived higher level of crime or homelessness.

But this perception — true or not — has an impact not only on the people who live there, but also on the future of the neighborhood itself in terms of development dollars and infrastructure repair.

"Oftentimes, to me, it seems to be a judgment call based on wealth," says Brandon Johnson, Wichita City Council member representing District I. "Especially here in District I, I've just seen folks label lower income parts of town as a bad part of town. ... It's where you don't see the types of investment and development going on. Where neighborhoods may look a little rundown or not well taken care of."

Unfortunately for these pockets of the city, such labels can often be enough to detract private investments. Without enough public funds — or a private investor willing to try something new — these areas fall further behind as dollars go toward projects either downtown or in more affluent neighborhoods.

There are opportunities available to help lower-income, under-invested areas get the support they need to improve and overcome perceived stigma.

PUBLIC & PRIVATE INVESTMENT

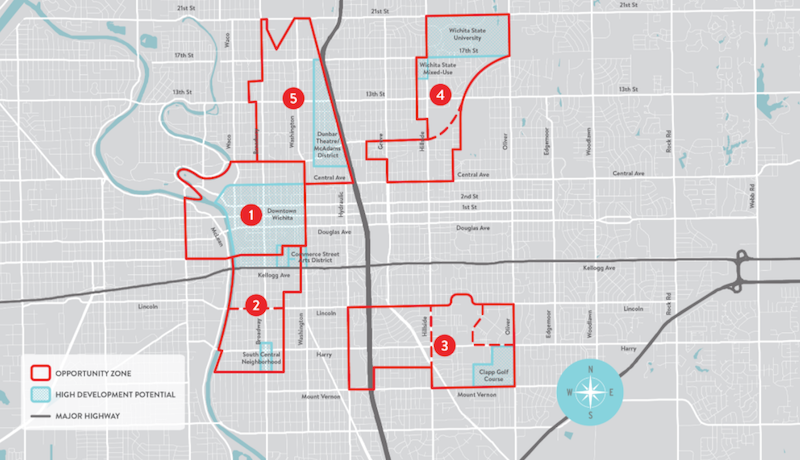

Across Wichita, there are neighborhoods labeled as "opportunity zones." These are locations with special tax incentives offered to developers who decide to invest in these areas. They range from south Wichita to northeast Wichita, near Wichita State University back to downtown.

The impact of these opportunity zones, which were set in 2017, is still unfolding, but downtown was attracting investment long before its designation. Since 2010, downtown had generated $108 million in public investment, spurring on $681 million in private investment.

Johnson says this was largely thanks to public-private partnerships and planning going back over a decade, including the Project Downtown master plan.

"Downtown was a ghost town," he says. "Now we see more than a billion dollars spent — a lot of that in the private sector."

The public sector's role was to improve infrastructure like streets and to partner with private investors on things like Naftzger Park and the Chester Lewis Reflection Park.

Private dollars have been responsible for the development itself, with tax incentives from the opportunity zone. But these projects have largely focused on downtown, where huge investments like Old Town and Intrust Bank Arena have already been made. Other opportunity zones haven't necessarily seen that level of investment.

"I've been trying to talk more about an equitable spending model, which would spend dollars where we've neglected," Johnson says. "The conversation that many people have about a rising tide lifting all ships, we don't ever talk about what the ocean floor looks like. So sometimes there's a trench and you need to put more water in that area to raise those boats up to be equal with everyone else before everyone starts to rise."

While the city's Capital Improvement Plan (CIP) lays out funding for infrastructure improvements, Johnson says more needs to be done to direct funding toward under-developed areas.

He says in some parts of Wichita, roads haven’t ever been paved — and in others, significant improvement hasn’t occurred in decades. A recent $4 million investment in 9th street between Hillside and I-135 was a start, but on 17th Street between Grove and I-135, it still floods nearly during heavy rainfall.

For the private sector's part, there are ways for development to spark change in an area. Johnson says a good example of this is Revolutsia, a storage container park built at Central and Volutsia, adjacent to opportunity zone 4 on the map.

"Once you get somebody who actually invests like that, you begin to see other people take interest — especially if it's successful," Johnson says. "Now you see more private sector [investment] coming in. Fidelity opened a branch in Revolutsia last year, Elite Staffing moved to Central and Grove, and more development is happening closer to Hillside."

EDITOR'S NOTE: The Bastian family, which owns Fidelity Bank, also funds The Chung Report

Development is often seen as a good thing. New infrastructure, innovative developments, improved property values and more business. But uncontrolled development can create issues with the residents of a specific area, pricing them out of their homes or forcing them to move to an entirely different part of the city.

This is gentrification.

DEFINING GENTRIFICATION

Gentrification is often tied to the improvement of an urban, lower-income area to meet middle class standards. Small, incremental change can help an area along while helping residents of that area, as well. But rapid change can price people out of neighborhoods they call home.

"For me, gentrification is when you change an area so much so that the current inhabitants can no longer afford to stay there," Johnson says. "At some point, at least one person in the neighborhood may not be able to afford to stay there. And to me, I don't want to see anyone lose, but that's kind of the reality of what the development may or may not bring."

While it's mostly been an issue in larger cities like Chicago and New York, gentrification can happen anywhere. In Wichita, it has gone hand-in-hand with redlining and segregation to particularly impact the black community.

"Areas that historically were red-lined are still either poor or over-gentrified right now," Johnson says. "[In the 1930s,] downtown was black Wichita. When you look at it, you don't see that anymore, except for the African-American Museum. Black Wichitans were moved into Northeast Wichita. And then with the red lining, there was no lending. Those neighborhoods were deemed bad. So generationally, it just became what it is now."

Fortunately, there are some safeguards against ramping up property taxes in up-and-coming areas. The state of Kansas implemented a property tax lid in 2017, and reinforced the law earlier this year, requiring municipalities to hold a public election to increase the property tax rate. This allows for more public oversight on local property tax hikes.

But even with these protections in place, increased property values could still affect the most vulnerable. Development that avoids gentrification becomes particularly difficult when you consider residents on fixed income.

"And in some of these older, established areas, that's what you have a lot of," Johnson says. "A lot of seniors or folks who maybe even have a disability on fixed income who can't get more dollars."

There are also positive examples of development in these neighborhoods. Johnson says the Rock the Block project with Habitat for Humanity has done a lot to improve an area bounded by 13th and 9th Streets and Hillside and Grove Streets. He says Mennonite Housing has also made a significant housing investment west of that area, while Power CDC has invested millions of dollars within the larger community to the north and west.

"Habitat for Humanity has been doing some amazing work," Johnson says. "More than 50 homes built, hundreds of kids, new families there."

While Rock the Block has increased property values, Johnson says it has also led to grants to help other nearby residents improve their homes with new siding, windows and driveways.

"There's a new sense of pride," Johnson says. "People are taking care of their properties, and I haven't seen people forced out just yet."

IMPROVING AREAS WITHOUT EXCLUDING PEOPLE

While avoiding gentrification completely may be difficult while seeking to develop within an area, Johnson says good communication is critical to ensure people who live there do not feel alienated.

"If you're developing a strip center or a small office space, talk to the community," he says. "See what they need. Because in the end, it benefits you and the community. If they need a grocery store and you put in a grocery store, they're going to use it. So you're going to get their traffic and they're going to take care of it because they value and they had input on it. We need to have more of those dialogues."

Johnson says it also helps if a development offers direct engagement with the people who live there. He says Fairmount Coffee on 17th Street is a good example because it offers a clean, affordable gathering space that also provides jobs to local residents.

"Those are the types of projects I think you do with a small business that improves the community," he says. "I think it will increase property values to an extent but, again, you're not pushing out and people get engaged in that way."

From a resident standpoint, Johnson says it's best to be proactive and look ahead to what's happening in your area. Watch meetings, talk with your council member and keep up with local news to find out when development might impact you or your neighborhood.

"The best thing to do is to get involved," Johnson says. "Reach out to your elected council member or mayor and just ask, and we can just send you an update of things that are going on."